Sacred Texts Hinduism Index Previous Next

COMPARED with the information collected above regarding the origin and the history of Âpastamba's Dharma-sûtra, the facts which can be brought to bear on Gautama's Institutes are scanty and the conclusions deducible from them somewhat vague. There are only two points, which, it seems to me, can be proved satisfactorily, viz. the connection of the work with the Sâma-veda and a Gautama Karana, and its priority to the other four Dharma-sûtras which we still possess. To go further appears for the present impossible, because very little is known regarding the history of the schools studying the Sâma-veda, and because the Dharmasâstra not only furnishes very few data regarding the works on which it is based, but seems also, though not to any great extent, to have been tampered with by interpolators.

As regards its origin, it was again Professor Max Müller, who, in the place of the fantastic statements of a fabricated tradition, according to which the author of the Dharmasâstra is the son or grandson of the sage Utathya, and the grandson or great-grandson of Usanas or Sukra, the regent of the planet Venus, and the book possessed generally binding force in the second or Tretâ Yuga 1, first put forward a rational explanation which, since, has been adopted by all other writers on Sanskrit literature. He says, Hist. Anc. Sansk. Lit., p. 134, 'Another collection of Dharma-sûtras, which, however, is liable to critical doubts, belongs

to the Gautamas, a Karana of the Sâma-veda.' This assertion agrees with Kumârila's statement, that the Dharmasâstra of Gautama and the Grihya-sûtra of Gobhila were (originally) accepted (as authoritative) by the Khandogas or Sâmavedins alone 1. Kumârila certainly refers to the work known to us. For he quotes in other passages several of its Sûtras 2.

That Kumârila and Professor Max Müller are right, may also be proved by the following independent arguments. Gautama's work, though called Dharmasâstra or Institutes of the Sacred Law, closely resembles, both in form and contents, the Dharma-sûtras or Aphorisms on the Sacred Law, which form part of the Kalpa-sûtras of the Vedic schools of Baudhâyana, Âpastamba, and Hiranyakesin. As we know from the Karanavyûha, from the writings of the ancient grammarians, and from the numerous quotations in the Kalpa-sûtras and other works on the Vedic ritual, that in ancient times the number of Vedic schools, most of which possessed Srauta, Grihya, and Dharma-sûtras, was exceedingly great, and that the books of many of them have either been lost or been disintegrated, the several parts being torn out of their original connection, it is not unreasonable to assume that the aphoristic law-book, usually attributed to the Rishi Gautama, is in reality a manual belonging to a Gautama Karana. This conjecture gains considerably in probability, if the fact is taken into account that formerly a school of Sâma-vedîs, which bore the name of Gautama, actually existed. It is mentioned in one of the redactions of the Karanavyûha 3 as a subdivision of the Rânâyanîya school. The Vamsa-brâhmana of the Sâma-veda, also, enumerates four members of the Gautama family among the teachers who handed down the third Veda, viz. Gâtri Gautama, Sumantra Bâbhrava

[paragraph continues] Gautama, Samkara Gautama, and Râdha Gautama 1, and the existing Srauta and Grihya-sûtras frequently appeal to the opinions of a Gautama and of a Sthavira Gautama 2. It follows, therefore, that at least one, if not several Gautama Karanas, studied the Sâma-veda, and that, at the time when the existing Sûtras of Lâtyâyana and Gobhila were composed, Gautama Srauta and Grihya-sûtras formed part of the literature of the Sâma-veda. The correctness of the latter inference is further proved by Dr. Burnell's discovery of a Pitrimedha-sûtra, which is ascribed to a teacher of the Sâma-veda, called Gautama 3.

The only link, therefore, which is wanting in order to complete the chain of evidence regarding Gautama's Aphorisms on the sacred law, and to make their connection with the Sâma-veda perfectly clear, is the proof that they contain special references to the latter. This proof is not difficult to furnish, For Gautama has borrowed one entire chapter, the twenty-sixth, which contains the description of the Krikkhras or difficult penances from the Sâmavidhâna, one of the eight Brâhmanas of the Sâma-veda 4. The agreement of the two texts is complete except in the Mantras (Sûtra 12) where invocations of several deities, which are not usually found in Vedic writings, have been introduced. Secondly, in the enumeration of the purificatory texts, XIX, 12, Gautama shows a marked partiality for the Sâma-veda. Among the eighteen special texts mentioned, we find not less than nine Sâmans. Some of the latter, like the Brihat, Rathantara, Gyeshtha, and Mahâdivâkîrtya chants, are mentioned also in works belonging to the Rig-veda and the Yagur-veda, and are considered by Brâhmanas of all schools to possess great efficacy. But others, such as the Purushagati, Rauhina, and Mahâvairâga Sâmans, have hitherto not been met with anywhere but in books belonging to the Sâma-veda, and

do not seem to have stood in general repute. Thirdly, in two passages, I, 50 and XXV, 8; the Dharmasâstra prescribes the employment of five Vyâhritis, and mentions in the former Sûtra, that the last Vyâhriti is satyam, truth. Now in most Vedic works, three Vyâhritis only, bhûh, bhuvah, svah, are mentioned; sometimes, but rarely, four or seven occur. But in the Vyâhriti Sâman, as Haradatta points out 1, five such interjections are used, and satyam is found among them. It is, therefore, not doubtful, that Gautama in the above-mentioned passages directly borrows from the Sâma-veda. These three facts, taken together, furnish, it seems to me, convincing proof that the author of our Dharmasâstra was a Sâma-vedi. If the only argument in favour of this conclusion were, that Gautama appropriated a portion of the Sâmavidhâna, it might be met by the fact that he has also taken some Sûtras (XXV, 1-6), from the Taittirîya Âranyaka. But his partiality for Sâmans as purificatory texts and the selection of the Vyâhritis from the Vyâhriti Sâman as part of the Mantras for the initiation (1, 50), one of the holiest and most important of the Brahmanical sacraments, cannot be explained on any other supposition than the one adopted above.

Though it thus appears that Professor Max Müller is right in declaring the Gautama Dharmasâstra to belong to the Sâma-veda, it is, for the present, not possible to positively assert, that it is the Dharma-sûtra of that Gautama Karana, which according to the Karanavyûha quoted in the Sabdakalpadruma of Râdhâkanta, formed a subdivision of the Rânâyanîyas. The enumeration of four Âkâryas, bearing the family-name Gautama, in the Vamsa-brâhmana, and Lâtyâyana's quotations from two Gautamas, make it not unlikely, that several Gautama Karanas once existed among the Sâma-vedi Brâhmanas, and we possess no means for ascertaining to which our Dharmasâstra must be attributed. Further researches into the history of the schools of the Sâma-veda must be awaited until we can do more. Probably the living tradition of the Sâma-vedîs of

[paragraph continues] Southern India and new books from the South will clear up what at present remains uncertain.

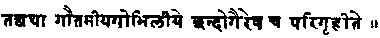

In concluding this subject I may state that Haradatta seems to have been aware of the connection of Gautama's law-book with the Sâma-veda, though he does not say it expressly. But he repeatedly and pointedly refers in his commentary to the practices of the Khandogas, and quotes the Grihya-sûtra of the Gaiminîyas 1, who are a school of Sâma-vedîs, in explanation of several passages. Another southern author, Govindasvâmin (if I understand the somewhat corrupt passage correctly), states directly in his commentary on Baudhâyana I, 1, 2, 6, that the Gautamîya Dharmasâstra was originally studied by the Khandogas alone 2.

In turning now to the second point, the priority of Gautama to the other existing Dharma-sûtras, I must premise that it is only necessary to take into account two of the latter, those of Baudhâyana and Vasishtha. For, as has been shown above in the Introduction to Âpastamba, the Sûtras of the latter and those of Hiranyakesin Satydshâdha are younger than Baudhâyana's. The arguments which allow us to place Gautama before both Baudhâyana and Vasishtha are, that both those authors quote Gautama as an authority on law, and that Baudhâyana has transferred a whole chapter of the Dharmasâstra to his work, which Vasishtha again has borrowed from him.

As regards the case of Baudhâyana, his references to Gautama are two, one of which can be traced in our Dharmasâstra. In the discussion on the peculiar customs prevailing in the South and in the North of India (Baudh. Dh. 1, 2, 1-8) Baudhâyana expresses himself as follows:

'1. There is a dispute regarding five (practices) both in the South and in the North.

'2. We shall explain those (peculiar) to the South.

'3. They are, to eat in the company of an uninitiated person, to eat in the company of one's wife, to eat stale food, to marry the daughter of a maternal uncle or of a paternal aunt.

'4. Now (the customs peculiar) to the North are, to deal in wool, to drink rum, to sell animals that have teeth in the upper and in the lower jaws, to follow the trade of arms and to go to sea.

'5. He who follows (these practices) in (any) other country than the one where they prevail commits sin.

'6. For each of these practices (the rule of) the country should be (considered) the authority.

'7, Gautama declares that this is false.

'8. And one should not take heed of either (set of practices), because they are opposed to the tradition of those learned (in the sacred law 1).'

From this passage it appears that the Gautama Dharma-sûtra, known to Baudhâyana, expressed an opinion adverse to the authoritativeness of local customs which might be opposed to the tradition of the Sishtas, i.e. of those who really deserve to be called learned in the law. Our Gautama teaches the same doctrine, as he says, XI, 20, 'The laws of countries, castes, and families, which are not opposed to the (sacred) records, have also authority.'

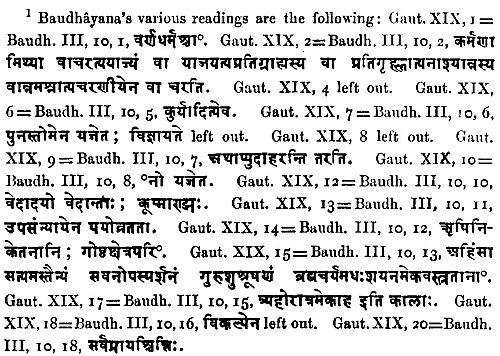

As clear as this reference, is the case in which Baudhâyana has borrowed a whole chapter of our Dharmasâstra. The chapter in question is the nineteenth, which in Gautama's work forms the introduction to the section on penances and expiation. It is reproduced with a number of various readings 1 in the third Prasna of Baudhâyana's Dharma-sûtra, where it forms the tenth and last Adhyâya. Its contents, and especially its first Sûtra which connects the section on penances with the preceding ones on the law of castes and orders, make it perfectly clear that its proper position can only be at the beginning of the rules on expiation, not in the middle of the discussion, as Baudhâyana places it 2. This circumstance alone would be sufficient to prove that Baudhâyana is the borrower, not Gautama, even if the name of the latter did not occur in Baudhâyana's Dharma-sûtra. But the character of many of Baudhâyana's readings, especially of those in Sûtras 2, 10, 5 11, 13, and 15, which, though supported by all the MSS. and Govindasvâmin's commentary, appear to have arisen chiefly through clerical mistakes or carelessness, furnishes

even an additional argument in favour of the priority of Gautama's text. It must, however, be admitted that the value of this point is seriously diminished by the fact that Baudhâyana's third Prasna is not above suspicion and may be a later addition 1.

As regards Baudhâyana's second reference to Gautama, the opinion which it attribute, to the latter is directly opposed to the teaching of our Dharmasâstra. Baudhâyana gives II, 2, 4, 16 the rule that a Brâhmana who is unable to maintain himself by teaching, sacrificing, and receiving gifts, may follow the profession of a Kshatriya, and then goes on as follows 2:

'17. Gautama declares that he shall not do it. For the duties of a Kshatriya are too cruel for a Brâhmana.'

As the commentator Govindasvâmin also points out, exactly the opposite doctrine is taught in our Dharmasâstra, which (VII, 6) explicitly allows a Brâhmana to follow, in times of distress the occupations of a Kshatriya. Govindasvâmin explains this contradiction by assuming that in this case Baudhâyana 2 cites the opinion, not of the author of our Dharmasâstra, but of some other Gautama. According to what has been said above 3, the existence of two or even more ancient Gautama Dharma-sûtras is not very improbable, and the commentator may possibly be right. But it seems to me more likely that the Sûtra of Gautama (VII, 6) which causes the difficulty is an interpolation, though Haradatta takes it to be genuine. My reason for considering it to be spurious is that the permission to follow the trade of arms is opposed to the sense of two other rules of Gautama. For the author states at the end of the same chapter on times of distress, VII, 25, that 'even a Brâhmana may take up arms when his life is in danger.' The meaning of these words can only be, that a Brâhmana must not fight under any other circumstances.

[paragraph continues] But according to Sûtra 6 he is allowed to follow the occupations of a Kshatriya, who lives by fighting. Again, in the chapter on funeral oblations, XV, 18, those Brâhmanas 'who live by the use of the bow' are declared to defile the company at a funeral dinner. It seems to me that these two Sûtras, taken together with Baudhâyana's assertion that Gautama does not allow Brâhmanas to become warriors, raise a strong suspicion against the genuineness, of VII. 6, and I have the less hesitation in rejecting the latter Sûtra, as there are several other interpolated passages in the text received by Haradatta 1. Among them I may mention here the Mantras in the chapter taken from the Sâmavidhâna, XXVI, 12, where the three invocations addressed to Siva are certainly modern additions, as the old Sûtrakâras do not allow a place to that or any other Paurânic deity in their works. A second interpolation will be pointed out below.

The Vâsishtha Dharma-sûtra. shows also two quotations from Gautama; and it is a curious coincidence that, just as in the case of Baudhâyana's references, one of them only can be traced in our Dharmasâstra. Both the quotations occur in the section on impurity, Vâs. IV, where we read as follows ' 2:

'33. If an infant aged less than two years, dies, or in the case of a miscarriage, the impurity of the Sapindas (lasts) for three (days and) nights.

'34. Gautama declares that (they become) pure at once (after bathing).

'35. If (a person) dies in a foreign country and (his Sapindas) hear (of his death) after the lapse of ten days, the impurity lasts for one (day and) night.

'36. Gautama declares that if a person who has kindled the sacred fire dies on a journey, (his Sapindas) shall again

celebrate his obsequies, (burning a dummy made of leaves or straw,) and remain impure (during ten days) as (if they had actually buried) the corpse.'

The first of these two quotations or references apparently points to Gautama Dh. XIV, 44, where it is said, that 'if an infant dies, the relatives shall be pure at once.' For, though Vasishtha's Sûtra 34, strictly interpreted, would mean, that Gautama declares the relatives to be purified instantaneously, both if an infant dies and if a miscarriage happens, it is also possible to refer the exception to one of the two cases only, which are mentioned in Sûtra 33. Similar instances do occur in the Sûtra style, where brevity is estimated higher than perspicuity, and the learned commentator of Vasishtha does not hesitate to adopt the same view. But, as regards the second quotation in Sûtra 36, our Gautama contains no passage to which it could possibly refer. Govindasvâmin, in his commentary on the second reference to Gautama in Baudhâyana's Dharmasâstra II, 2, 71, expresses the opinion that this Sûtra, too, is taken from the 'other' Gautama Dharma-sûtra, the former existence of which he infers from Baudhâyana's passage. And curiously enough the regarding the second funeral -actually is found in the metrical Vriddha-Gautama 1 or Vaishnava Dharma-sâstra, which, according to Mr. Vâman Shâstrî Islâmpurkar 2, forms chapters 94-115 of the Asvamedha-parvan of the Mahâbhârata in a Malayâlam MS. Nevertheless, it seems to me very doubtful if Vasishtha did or could refer to this work. As the same rule occurs sometimes in the Srauta-sûtras 3, I think it more probable that the Srauta-sûtra of the Gautama school is meant. And it is significant that the Vriddha-Gautama declares its teaching to be kalpakodita 'enjoined in the Kalpa or ritual.'

Regarding Gautama's nineteenth chapter, which appears in the Vasishtha Dharmasâstra as the twenty-second, I have

already stated above that it is not taken directly from Gautama's work, but from Baudhâyana's. For it shows most of the characteristic readings of the latter. But a few new ones also occur, and some Sûtras have been left out, while one new one, a well-known verse regarding the efficacy of the Vaisvânara vratapati and of the Pavitreshti, has been added. Among the omissions peculiar to Vasishtha, that of the first Sûtra is the most important, as it alters the whole character of the chapter, and removes one of the most convincing arguments as to its original position at the head of the section on penances. Vasishtha places it in the beginning of the discussion on penances which are generally efficacious in removing guilt, and after the rules on the special penances for the classified offences.

These facts will, I think, suffice to show that the Gautama Dharmasâstra may be safely declared to be the. oldest of the existing works on the sacred law 1. This assertion must, however, not be taken to mean, that every single one of its Sûtras is older than the other four Dharma-sûtras. Two interpolations have already been pointed out above 2, and another one will be discussed presently. It is also not unlikely that the wording of the Sûtras has been changed occasionally. For it is a suspicious fact that Gautama's language agrees closer with Pânini's rules than that of Âpastamba and Baudhâyana. If it is borne in mind that Gautama's work has been torn out of its original connection, and from a school-book has become a work of general authority, and that for a long time it has been studied by Pandits who were brought up in the traditions of classical grammar, it seems hardly likely that it could retain much of its ancient peculiarities of language. But I do not think that the interpolations and alterations can have affected the general character of the book very much. It is too methodically planned and too carefully arranged to admit of any very great changes. The fact, too, that in

the chapter borrowed by Baudhâyana the majority of the variae lectiones are corruptions, not better readings, favours this view. Regarding the distance in time between Gautama on the one hand, and Baudhâyana and Vasishtha on the other, I refer not to hazard any conjecture, as long as the position of the Gautamas among the schools of the Sâma-veda has not been cleared up. So much only can be said that Gautama probably was less remote from Baudhâyana than from Vasishtha. There are a few curious terms and rules in which the former two agree, while they, at the same time, differ from all other known writers on Dharma. Thus the term bhikshu, literally a beggar, which Gautama 1 uses to denote an ascetic, instead of the more common yati or sannyâsin, occurs once also in Baudhâyana's Sûtra. The same is the case with the rule, III, 13, which orders the ascetic not to change his residence during the rains. Both the name bhikshu and the rule must be very ancient, as the Gainas and Buddhists have borrowed them, and have founded on the latter their practice of keeping the Vasso, or residence in monasteries during the rainy season.

As the position of the Gautamas among the Sâman schools is uncertain, it will, of course, be likewise inadvisable to make any attempt at connecting them with the historical period of India. The necessity of caution in this respect is so obvious that I should not point it out, were it not that the Dharmasâstra contains one word, the occurrence of which is sometimes considered to indicate the terminus a quo for the dates of Indian works. The word to which I refer is Yavana. Gautama quotes, IV, 21, an opinion of 'some,' according to which a Yavana is the offspring of a Sûdra male and a Kshatriya female. Now it is well known that this name is a corruption of the Greek Ἰαϝων, an Ionian, and that in India it was applied, in ancient times, to the Greeks, and especially to the early Seleucids who kept up intimate relations with the first Mauryas, as well as later to the Indo-Bactrian and Indo-Grecian kings who from the beginning of the second century B. C. ruled

over portions of north-western India. And it has been occasionally asserted that an Indian work, mentioning the Yavanas, cannot have been composed before 300 B. C., because Alexander's invasion first made the Indians acquainted with the name of-the Greeks. This estimate is certainly erroneous, as there are other facts, tending to show that at least the inhabitants of north-western India became acquainted with the Greeks about 200 years earlier 1. But it is not advisable to draw any chronological conclusions from Gautama's Sûtra, IV, 21. For, as, pointed out in the note to the translation of Sûtra IV, 18, the whole section with the second enumeration of the mixed castes, IV, 17-21, is probably spurious.

The information regarding the state of the Vedic literature, which the Dharmasâstra furnishes, is not very extensive. But some of the items are interesting, especially the proof that Gautama knew the Taittirîya Âranyaka, from which he took the first six Sûtras of the twenty-fifth Adhyâya; the Sâmavidhâna Brâhmana, from which the twenty-sixth Adhyâya has been borrowed; and the Atharvasiras, which is mentioned XIX, 12. The latter word denotes, according to Haradatta, one of the Upanishads of the Atharva-veda, which usually are not considered to belong to a high antiquity. The fact that Gautama and Baudhâyana knew it, will probably modify this opinion. Another important fact is that Gautama, XXI, 7, quotes Manu, and asserts that the latter declared it to be impossible to expiate the guilt incurred by killing a Brâhmana, drinking spirituous liquor, or violating a Guru's bed. From this statement it appears that Gautama knew an ancient work on law which was attributed to Manu. It probably was the foundation of the existing Mânava Dharmasâstra 2. No other teacher on law, besides Manu, is mentioned by name. But the numerous references to the opinions of 'some' show that Gautama's work was not the first Dharma-sûtra.

In conclusion, I have to add a few words regarding the materials on which the subjoined translation is based. The text published by Professor Stenzler for the Sanskrit Text Society has been used as the basis 1. It has been collated with a rough edition, prepared from my own MSS. P and C, a MS. belonging to the Collection of the Government of Bombay, bought at Belgâm, and a MS. borrowed from a Puna Sâstrî. But the readings given by Professor Stenzler and his division of the Sûtras have always been followed in the body of the translation. In those cases, where the variae lectiones of my MSS. seemed preferable, they have been given and translated in the notes. The reason which induced me to adopt this course was that I thought it more advisable to facilitate references to the printed Sanskrit text than to insist on the insertion of a few alterations in the translation, which would have disturbed the order of the Sûtras. The notes have been taken from the above-mentioned rough edition and from my MSS. of Haradatta's commentary, called Gautamîyâ Mitâksharâ, which are now deposited in the India Office Library, Sansk. MSS. Bühler, Nos. 165-67.

xlix:1 Manu III, 19; Colebrooke, Digest of Hindu Law, Preface, p. xvii (Madras ed.); Anantayagvan in Dr. Burnell's Catalogue of Sanskrit MSS., (p. 57; Pârâsara, Dharmasâstra I, 22 (Calcutta ed.).

l:1 Tantravârttika, p. 179 (Benares ed.),

.

.

l:2 Viz. Gautama I, 2 on p. 143; II, 45-46 on p. 112, and XIV, 45-46 on p. 109.

l:3 Max Müller, Hist. Anc. Sansk. Lit., p. 374.

li:1 See Burnell, Vamsa-brâhmana, pp. 7, 9, 11, and 12.

li:2 See the Petersburg Dictionary, s. v. Gautama; Weber, Hist. Ind. Lit., p. 77 (English ed.); Gobhila Grihya-sûtra III, 10, 6.

li:3 Weber, Hist. Ind. Lit., p. 84, note 89 (English ed.)

lii:1 See Gautama I, 50, note.

liii:1 A Grihya-sûtra. of the Gaiminîyas has been discovered by Dr. Burnell with a commentary by Srînivâsa. He thinks that the Gaiminîyas are a Sûtra-sâkhâ of the Sâtyâyana-Talavakâras.

liii:2 My transcript has been made from the MS. presented by Dr. Burnell, the discoverer of the work, to the India Office Library. The passage runs as follows: Yathâ vi bodhâkyanîyam dharmasâstram kaiskid eva pathyamânam sarvâdhikâram bhavati tathâ gautamîye gobhilîye (?) khandogair eva pathyate || vâsishtham tu bahvrikair eva ||

lv:1

.

.

lv:2 Baudhâyana's treatment of the subject of penances is very unmethodical. He devotes to them the following sections: II, 1-2; II, 2, 3, 48-53; II, 2, 4; III, 5-10; and the greater part of Prasna IV.

lvi:1 See Sacred Books of the East, vol. xiv, p. xxxiv seq.

lvi:2 Baudh. Dh. II, 2, 4, 17.

lvii:1 In some MSS. a whole chapter on the results of various sins in a second birth is inserted after Adhyâya XIX. But Haradatta does not notice it; see Stenzler, Gautama, Preface, p. iii.

lvii:2 In quoting the Vâsishtha Dh. I always refer to the Benares edition, which is accompanied by the Commentary of Krishnapandita Dharmâdhikârin, called Vidvanmodinî.

lviii:1 Dharmasâstra samgraha (Gîbânand), p. 627, Adhy. 20, 1 seqq.

lviii:2 Parâsara Dharma Samhitâ (Bombay Sansk. Series, No. xlvii), vol. i, p. 9.

lviii:3 See e.g. Âp. Sr. Sû.

lix:1 Professor Stenzler, too, had arrived independently at this conclusion, see Grundriss der Indo-Ar. Phil. und Altertumsk., vol. ii, Pt. 8, p. 5.

lx:1 Gaut. Dh. III, 2, 11; see also Weber, Hist. Ind. Lit., P.327 (English ed.)

lxi:1 See my Indian Studies, No. iii, p. 26, note 1.

lxi:2 Compare also Sacred Books of the East, vol. xxv, p. xxxiv seq.

lxii:1 The Institutes of Gautama, edited with an index of words by A. F. Stenzler, London, 1876.